The Black Swan: Summary Review & Takeaways

This is a summary review of Black Swan containing key details about the book.

What is Black Swan About?

Black Swan covers subjects relating to knowledge, aesthetics, as well as ways of life, and uses elements of fiction and anecdotes from the author's life to elaborate his theories. It focuses on the extreme impact of rare and unpredictable outlier events—and the human tendency to find simplistic explanations for these events, retrospectively. Taleb calls this the Black Swan theory.

The book asserts that a "Black Swan" event depends on the observer: for example, what may be a Black Swan surprise for a turkey is not a Black Swan surprise for its butcher. Hence the objective should be to "avoid being the turkey", by identifying areas of vulnerability in order to "turn the Black Swans white".

Who is the Author of Black Swan?

Nassim Nicholas Taleb is a Lebanese-American essayist, mathematical statistician, former option trader, risk analyst, and aphorist whose work concerns problems of randomness, probability, and uncertainty. The Sunday Times called his 2007 book The Black Swan one of the 12 most influential books since World War II

What are the main summary points of The Black Swan?

Here are some key summary points from the book:

- The term “black swans” is used to describe highly consequential, yet highly unlikely events that can only easily be explained in hindsight.

- Tech, business, science, and even culture have all been shaped by the appearance of black swans.

- Black swans are becoming more consequential due to the world being more connected.

- Humans are naturally subject to numerous blind spots, illusions, and biases.

- The bell curve is a standard statistical tool that is often misused, resulting in a negative bias that ignores black swans.

- The “power law distribution” is a statistical tool that is better at modeling important phenomena.

- Much of the time, expert advice is useless; forecasting is deemed a pseudoscience.

- It is possible to train yourself to appreciate randomness and overcome cognitive biases, but it takes work.

- Positive black swans do exist; Weigh up the odds so you can avoid the negative black swans.

What are key takeaways from The Black Swan?

Takeaway#1. The Extraordinary Can Become Ordinary

Prior to 169, Europeans thought that all swans were white, since every swan they’d seen and heard about was white. But when the Dutch explorer William de Vlamingh landed in Australia, he discovered otherwise. Amongst the strange creatures found on the other side of the world, such as the hopping kangaroo and the teddy bear-like koala bear, he also came across black swans. This discovery forced people in Europe to revise their concept of the swan being white and over time, black swans came to be, though perhaps not common, ordinary, as if there was never any question about swans being white or black.

This is a common pattern: Unlikely events and inventions seem impossible when they lie in the unknown or in the future, but once they happen, people soon absorb the previously unknown into their concept of the world with the extraordinary (such as cars, planes, the Internet, and working from home due to Covid-19 lockdown) becoming ordinary.

Experts and forecasters kick themselves for not predicting the now obvious occurrences of what, back then, seemed unlikely and perhaps even unimaginable. Just think of World War I and World War II, 9/11, the 90’s dot-com bubble crash, and now, Covid-19 and lockdown. No one would have imagined in the run-up to Christmas, 2019 that next spring, people would be stuck at home for 3 months, isolating to stop the spread of a deadly virus. It’s not just inventions and events that seemingly come out of nowhere, though—think of cultural fads such as the Spice Girls and Harry Potter sweeping the world.

Looking back, it can seem inevitable that these occurrences would happen, so why wasn’t it thought possible beforehand? It all comes down to the human mind: Our brains are still programmed for life 200,000 years ago when we were hunter gatherers, and its primary function was to keep us alive long enough to reproduce. We haven’t had an upgrade and overhaul to create a new, ideal cognitive mechanism. So, our brain is simply not capable of processing the onslaught of confusing data thrown at it today, and in order to cope without getting overwhelmed, it over-simplifies using mental schemas, biases, self-deception, and heuristics. These mechanisms can come at a cost, as in the case of storytelling.

Takeaway#2. Being Aware of Our Misconceptions, Biases, and Theories

Passing down stories has long been a way for people to remember and make sense of the past and to inspire them for the future. But if you stop to think about it, are the stories that people have to tell due to hard work and lessons learned, or just plain old luck?

Today, when we read about successful people— be they entrepreneurs, film stars, musicians, or inventors—the story will often start in the present, after the person has gained success. The article or story then goes back in time to recount the person’s (usually) humble beginnings: They came from nothing but had a dream of riches and/or success, the dream/desire being their “dramatic need.” The story will recount how they overcame multiple obstacles, moving up the ladder of success, gaining the Hollywood mansion, the fancy cars, the perfect partner, and the amassed fortune, which has allowed early retirement. Sound familiar?

When entrepreneurs, authors, sports stars, etc. visit schools and universities recounting their success story, students sit in awe as they listen, thinking this person is an inspiration, a hero. But what if this person’s assumed “virtues” had nothing to do with success and everything to do with being in the right place at the right time? All too often, we underestimate luck in life although, ironically, we tend to overestimate it when it comes to games of chance.

Not all success is down to luck though; skill can be the key to success in some professions, but in others, luck governs how well you’ll do. Thinking of the successful entrepreneur or recording artist, consider people who came from similar backgrounds, had the same dream, and produced comparable work at the same time as the successful person... Why did the other person not reach the same heights of success? If it wasn’t down to a lack of desire, drive, or talent, it must have been down to not being in the right place at the right time? Sadly, the evidence is lost in history since these unsuccessful people don’t get to tell their story, and ultimately, their “failure” hides the evidence that would undercut the success story of the other person.

The human mind has many more simplifying schemas that lead to error, theories being a good example. When people have a theory, they seek evidence to confirm that theory, finding patterns that do not exist or conveniently jumping over discrepancies. This is known as “confirmation bias,” and it allows people to become overconfident and arrogant in their way of thinking (I know that my way is the only correct way of doing it!) and to forget to take randomness into account. They become limited in what they see, experiencing a sort of tunnel vision, and though they might turn to so-called experts for knowledge, these “experts” believe in the same theory and confirm one way of seeing. The insight gained can be worse than flipping a coin to learn who and what is correct since black swans are not taken into consideration.

Takeaway#3. Taking Extremes into Account

Our brain naturally tries to make the roughness of reality smoother. This can be a problem, depending on which side of the coin your observable fact or event falls into: “mediocristan” or “extremistan.”

These terms describe two extremely different classes of natural phenomena. Mediocristan refers to i phenomena which use standard statistical concepts like the “bell curve.” Extremistan, on the other hand,refers to an observable fact or event where a single, curve-distorting action, person, or event can radically twist the distribution. To understand extremistan better, just think of Buckingham Palace or the White House being used as a starting point when comparing family house sizes!

The difference between mediocristan and extremistan can be explained by thinking about the height of people versus ticket sales at movie theatres. People’s height varies such that you might have someone measuring 8ft tall and another just 2ft tall in your sample. However, this variation is limited: your data set is never going to include someone 1 inch tall or 2,000 ft tall! When it comes to movie ticket sales, though, your highs and lows can be very extreme compared to the middle (median value) of your sample—so extreme that using the bell curve to model the distribution will be misleading. In this case, it’s better to use the “power law” curve. The “power law” model ensures that an extreme event is not treated as an outlier and excluded from the data set but actually determines the shape of the curve.

Social facts and events cannot be modeled using the bell curve because there are far too many feedback loops, otherwise known as “social contagion,” in which movie sales keep getting bigger and bigger. They don’t just get a little bigger, they go through the roof with the distribution badly shaped, putting you in the realm of extremistan.

Takeaway#4. Being Aware of Phony Forecasting

Extremistan wouldn’t be so bad if it was possible to predict when these outliers were going to pop up and to what extreme, but it’s impossible to do this precisely. Just think about the biggest box office hits and the books that have taken the world by storm. No one could predict that Harry Potter or Fifty Shades of Grey would be written and then explode in wide popularity. Stock prices work in the same way; you can never be 100% certain when a crash is coming nor which stock will shoot up. Any “experts” who say they can always predict the price of stocks or commodities in years to come are quacks. Nobody knows for sure what the next “big thing” is going to be despite the so-called experts sharing their insider knowledge of what will happen in the future. Whether you want to call them forecasters, futurists, prophesiers, or fortune tellers, they usually miss the big important events that shape our lives and the world.

“Nerds and herds” are accountable for these errors, but it’s not really their fault since they can only work with the set of statistical tools in the way they have been taught. That’s why bell curves appear everywhere with disconfirming data explained away as “outliers,” “noise,” or “exogenous shocks.” Even Excel spreadsheets allow users to fit a regression line to any messy series of data. Add to this the fact that we humans tend to act like sheep, looking to experts in their specialized fields and rarely looking outside the box. It should be remembered, though, that some realms of expertise simply don’t exist because the facts and events are just too crazily random. This inability to explain and predict everything and anything can be too much for our brains to handle and highly discomforting to think about for any length of time. So, we apply a mental sedative which lets us think that the world is far more safe, organized, and consistent than it really is—that is, until something comes along to remind us that it’s a precarious world we live in.

Takeaway#5. Taming Black Swans

Using your new-found knowledge, you can tame, and potentially befriend, black swans. Be smart by remembering and recognizing the following as you go through life:

Keep your eyes out for black swans - notice when you are in extremistan rather than mediocristan territory.

Revise your beliefs when you come across evidence that goes against what you believe to be true. It’s ok to say “I was wrong.”

Avoid being arrogant and overly assertive and don’t fall into the nerd or herd category.

Don’t be a fool with your predictions. You’re more likely to predict with accuracy what your child wants for Christmas than you are the price of property, oil, or gold in the future.

You can’t know everything. It’s better to eliminate theories you know are wrong rather than spending all your time trying to find the truth.

Be wary of predictions that seem overly precise; the longer the forecast, the more room there is for prediction errors.

Put yourself in front of positive black swans and turn your back on negative black swans.Think of the phrase “bet pennies to win dollars” and look for irregularities that have more positive consequences than negative ones.

Gathering a plethora of confirming evidence doesn’t necessarily prove a theory; instead, look for disconfirming evidence that contradicts your theory.

Remember that you and the planet you live on exist because of black swans.

Book details

- Print length: 366 Pages

- Audiobook: 14 hrs and 20 mins

- Genre: Nonfiction, Economics, Business

What are the chapters in Black Swan?

Part one - Umberto Eco's antilibrary, or how we seek validation

Part two - We just can't predict

Part three - Thos gray swans of extremistan

Part four - The end.

What are good quotes from The Black Swan?

“The problem with experts is that they do not know what they do not know”

“Categorizing is necessary for humans, but it becomes pathological when the category is seen as definitive, preventing people from considering the fuzziness of boundaries”

" it is contagion that determines the fate of a theory in social science, not its validity.”

"We grossly overestimate the length of the effect of misfortune on our lives. You think that the loss of your fortune or current position will be devastating, but you are probably wrong. More likely, you will adapt to anything, as you probably did after past misfortunes."

“Missing a train is only painful if you run after it! Likewise, not matching the idea of success others expect from you is only painful if that’s what you are seeking.” (Meaning)

What do critics say?

Here's what one of the prominent reviewers had to say about the book: “[Taleb writes] in a style that owes as much to Stephen Colbert as it does to Michel de Montaigne. . . . We eagerly romp with him through the follies of confirmation bias [and] narrative fallacy.” — The Wall Street Journal

* The summary points above have been concluded from the book and other public sources. The editor of this summary review made every effort to maintain information accuracy, including any published quotes, chapters, or takeaways

Chief Editor

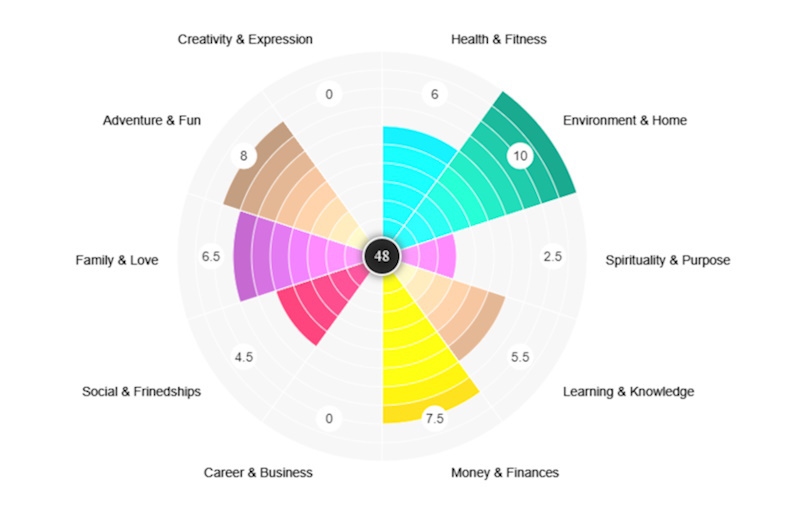

Tal Gur is an author, founder, and impact-driven entrepreneur at heart. After trading his daily grind for a life of his own daring design, he spent a decade pursuing 100 major life goals around the globe. His journey and most recent book, The Art of Fully Living, has led him to found Elevate Society.

Tal Gur is an author, founder, and impact-driven entrepreneur at heart. After trading his daily grind for a life of his own daring design, he spent a decade pursuing 100 major life goals around the globe. His journey and most recent book, The Art of Fully Living, has led him to found Elevate Society.